- Home

- Robert Weintraub

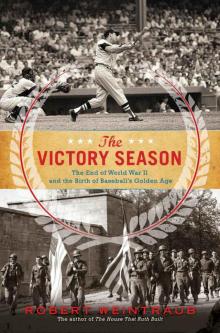

The Victory Season Page 14

The Victory Season Read online

Page 14

It was frustrating, for the papers were filled with new flying records and feats. One day, Transcontinental and Western Airways, soon to be renamed Trans World Airlines, operated its first international flight, connecting New York and Paris. The next, Heathrow Airport opened for business in London. One day, pilots landed in Cairo forty hours after taking off from Honolulu, 9,500 miles from island to desert. The next, a plane flew over the Arctic Circle, proving travel over the poles was possible. One day, a P-84 Thunderjet tore through the sky at 611 miles an hour, just shy of the record set earlier that same day in England, where an RAF pilot teased the limits of the sound barrier at 615 mph. The next, a mammoth navy Lockheed, nicknamed the Truculent Turtle, spent fifty-five hours in the air, traveling over eleven thousand miles, a mark that would stand until 1962.

But those same papers were also filled with reports of crashes, seemingly every day, one upon another. No carrier was spared. Eastern lost a DC-3 in Connecticut with all seventeen aboard killed, and two weeks later United suffered a similar crash in Wyoming, with twenty-one dead. A horrific crash killed all twenty-seven on board an American flight in the California desert in early March. A navy Privateer disappeared off the Florida coast with twenty-eight souls gone. The entire Lockheed Constellation fleet was grounded after a fire broke out on board a flight that crashed in Reading, Pennsylvania. Two hundred sixty-eight people lost their lives in fourteen separate crashes around the world in September alone.

Even the great aviator Howard Hughes fell from the sky, crashing an experimental reconnaissance plane onto the rooftops of several posh Beverly Hills homes on July 7. Hughes somehow survived, despite six broken ribs, a collapsed lung, and major burns. His British counterpart Geoffrey de Havilland Jr., renowned test pilot and son of the famous airplane designer and pioneer, was less fortunate, killed when his DH 108 broke up over the Thames estuary.

In one extraordinary incident, a pilot named Warren Berg was flying over Detroit when he was forced to bail out of his malfunctioning plane. As Berg descended, another passing plane became ensnarled in his chute and nosed toward the earth. Berg desperately deployed his reserve parachute, which slowed the plane just enough. It hit the ground roughly but not catastrophically. Incredibly, Berg’s broken ankle was the sole casualty.

So while aviation was undoubtedly the future, train travel was still the present, and omnipresent it was. Sure, occasionally there was danger here too—in late April in Naperville, Illinois, the Exposition Flyer slammed into a parked train at nearly 100 mph, killing forty-seven and ushering in an 80-mph rail-speed limit. But for the most part, the nation relied on its trains.

New York’s Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal were better known, but Union Station in St. Louis had emerged during the war as the most heavily used depot in the land, ferrying soldiers from across the nation’s breadbasket to either coast for embarkation overseas. About 1.5 million tickets were issued there each year between 1942 and 1945. All trains backed into the station, a method that had failed only once, when a troop train had gone too far and crashed through the glass and steel wall that separated the platform from the midway. With that kind of traffic, trains were oversold and late all the time. As the English writer G. K. Chesterton put it, “the only way to guarantee making a train is to miss the one before it.”

The long trip between St. Louis and the East Coast tested the baseball traveler’s constitution, but it was hardly a forced march. As writer Roger Kahn recalled, it was a “24-hour hegira. You traveled in a private car and ate in a private diner, and a drink was never farther away than a porter’s call button.” Said porters wore immaculate white suits, serving steak and chops in large portions and of higher quality than most players would get at home. The tables featured white linens, fresh-cut flowers, and fine silverware.

There were other benefits granted baseball teams that the average rail passenger didn’t get. If a train arrived at its stop late at night, it was usually sidetracked until breakfast, so the players could sleep in. Dining hours were extended, generally encompassing any time a player wanted anything to eat, and rules about merriment in the club car were overlooked when a ball club was on board.

An extraordinary set of circumstances the season before had illuminated the rivalry between the Cards and Dodgers, the vagaries of train travel, and Sam Breadon’s penchant for squeezing out every last nickel, all at the same time. St. Louis and Chicago were battling for the 1945 pennant, with Brooklyn traveling to Sportsman’s Park and then Wrigley Field, hoping to play spoiler. A game in the Land of the Cottonwood Tree, as St. Loo was called, was rained out, and rather than play an afternoon doubleheader the following day, as the rules stated, Breadon tried to pull in some extra gate by announcing a twi-night affair. As the Brooks were due in the Windy City the next day, they howled bloody murder. The late start meant that instead of traveling by sleeper train, the team would have to sit up all night in an uncomfortable freight car, the only possibility to avoid forfeiting the next day’s game.

Leo was a hurricane of anger. Even though his team stunk, a wartime collection of hangers-on and happy-to-be-heres, he psyched them into playing like the ’27 Yankees. “Look at that plush-lined bum up there in his private box,” he fumed, pointing at Breadon, who looked every inch the feudal baron with his fur coat and long cigar. “Fuckin’ Ol’ Moneybags is making you risk your arms and legs. Go make him pay for it!” Which the Dodgers did, sweeping the key twin bill.

The team arrived at Union Station well past midnight to find a dirty collection of freight cars hauling produce, but with no dining cars. The players were hardly used to such low-class conditions, but their discomfort paled when the engineer, a Cubs fan eager to speed the team to Chicago, pushed his clunker of a train too hard. At Manhattanville, Illinois, it crashed into a fuel tanker, and the front of the train was an inferno. The team escaped out the back, but the engineer, Charley Tegtmeyer, was killed.

Out in the cold, Durocher’s fury was palpable, the blaze highlighting the high fever in his eyes. “Breadon! He should be here to see what he caused,” Leo spat. Ironically, the Dodgers limped into Chicago and were in no condition to best the Cubbies, who went on to edge the Cards and Breadon for the pennant.

Ballplayers being ballplayers, they often found the time for lounge-car fisticuffs, whether seriously or for the sheer testosterone rush of brawling. Losses at the gaming table often precipitated violence. Guys would get angry and go after the winner, or merely rip up decks of cards, forcing someone to walk over to the club car for a new deck. “We usually ran out of cards on trips west,” remembered Buddy Lewis, who played for the Senators in 1946.

Train travel was a breeding ground for superstition too; Durocher, for example, never, ever slept in the upper berth, a fact a traveling secretary named Ed Staples found out the hard way back in the early ’40s. Nicknamed “Stables,” he took Leo’s bottom rack on the long trip out to St. Louis and sacked out, forcing Durocher to roust the conductor to find him a new cabin. When Ed finally awoke, Durocher unloaded upon him. “No wonder they call you ‘Stables,’” he roared. “You’re a horse’s ass!”

Generally, long train trips were moneymaking operations for Durocher, whose prowess at the card table ensured that he always had money he could then blow when the team got to the next city. His personal pigeon was Roscoe McGowen of the Times. Durocher would bluff the portly, scholarly scribe down to his shoes, and McGowen would curse Leo out in Shakespearean meter. At heart, he didn’t mind, for Lippy could be counted on to square things by picking up the tab at the bar or the nightclub.

Listening to music made the miles go down easier, and the Cards had an eclectic bunch of ears. Stan Musial loved boogie-woogie, while Red Schoendienst preferred Broadway hits like “Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life” and “Indian Love Call.” Howie Pollet and Harry Brecheen were partial to classical, especially Brahms and Beethoven. Max Lanier was a country guitar-picking aficionado, digging mournful records like “There’s a Chill on the Hill Tonight” an

d “I Pass the Graveyard at Midnight.” “If I could hear my music while I’m pitching, the bastards would never get a loud foul off me,” Lanier once said.

Pranking teammates was a timeless art, and every team had a jokester or two. Typical of the genre was a setup pulled by the A’s on a trip back from playing the Browns in late June. There was a quiet country kid on the roster, a reserve who seldom played or made a peep. Some of the boys put a bottle of White Lightning in his bag. They arranged for a sheriff from some backwater along the way to board the train and pretend to arrest the kid for operating a still. As he was dragged away in cuffs (the sheriff being a Method actor), he screamed his innocence. The other A’s, having satisfied themselves that the kid indeed could talk, laughed uproariously, then turned in for the night.

Since roster turnover had been so great after the demobilization, teams used the long train rides to get to know one another better and to talk about their wartime experiences. At least the guys who had it easy over there did; those who had seen serious combat were generally loath to talk about it with anyone who hadn’t been under fire, if at all.

Red Sox players who had been around the season before (eight players saw at least some time in both ’45 and ’46) told the newcomers about the day in August 1945 when the one-legged pitcher shut them down. His name was Bert Shepard, a fighter pilot shot down over Hamburg in May of 1944. It was opening day of the 55th Fighter Group’s baseball season, and the pitcher had volunteered to fly his thirty-fourth mission because it left at dawn, which would leave him enough time to get back for the game. He never made it. Instead, he took antiaircraft shrapnel in his right leg, and crash landed. A Luftwaffe surgeon named Ladislaus Loidl rescued Shepard from farmers armed with pitchforks and amputated his leg.

Wearing a prosthetic a fellow prisoner of war designed for him, Shepard returned to the States and set about playing ball. The Senators signed him when asked to do so by the War Department, and Shepard made several spring training appearances, his prosthetic awkward but manageable. On August 5, 1945, with the Sens trailing Boston 14–2, Shepard made his lone major league appearance, striking out the first man he faced, Catfish Metkovich, and pitching five and a third innings, giving up just three hits and one run.

The likes of Williams, Pesky, and DiMaggio must have had a good laugh at that, the peals ringing out over the passing countryside. Ol’ Catfish would have taken some ribbing—struck out by a one-legged pitcher! Metkovich, who earned his nickname (bestowed by Casey Stengel) by stepping on a bewhiskered fish and embedding its fin in his foot, no doubt turned as red as his uniform from the catcalls.

Shepard wasn’t on the ’46 Senators, but Buddy Lewis was. A vet with a healthy appetite for hijinks, Lewis had signed up for the Army Air Corps early in the war. One of his first assignments before going overseas was to fly VIPs to and from Washington, and when he met with his now ex-teammates before flying back, he told them to watch out for his farewell. As the game that afternoon got under way, a plane shot right over home plate of Griffith Stadium, very low, in defiance of all manner of ordinances. It wiggled its wings and flew off past the center field bleachers. It was Buddy, saying sayonara.

Lewis went off to the China-Burma-India theater to fly C-47s. He was told if he was shot down over Burma and survived, he should carry a baseball; because of the Japanese love of the game, they might spare him. He also carried a sizable portion of cocaine, as the native Burmese would do all manner of favors in return for a sniff or two.

Lewis was too good a pilot to get shot down, perhaps as good as Ted Williams. He won a Distinguished Flying Cross for his ability to land in small jungle clearings, often behind enemy lines, and “crossed the hump,” i.e., the Himalayas, numerous times. Crossing the hump was a particularly dangerous achievement, and only the best pilots made it routine. He flew an astounding 368 missions in his “Old Fox,” a plane he nicknamed for Clark Griffith, the Senators owner. “Everybody agreed he was the best transport pilot in the CBI theater,” Luke Sewell, then the manager of the St. Louis Browns, told the Washington Post in 1945 after flying with Lewis in Burma. “He set his big transport plane down on tiny strips that didn’t look big enough for a mosquito to land on. And he did it while he was talking baseball to me.”

Buddy still had his joie de vivre upon return, but he was affected by the conflict as so many others were. “When I came back from the war,” he reflected years later, “my whole philosophy of life was completely different. I had changed so much that baseball didn’t mean as much to me as it did before the war. I enlisted at 25, and came out a 30-year-old.”

Lewis was a third baseman before the war, playing next to, and rooming with, shortstop Cecil Travis. Lewis was a solid player—Travis was a star, one of the best players in Senators history. A sweet-swinging lefty that no less an expert than Ted Williams called “one of the five best left-handed hitters I ever saw,” Travis was a perennial All-Star, despite playing for the woeful Sens. In 1941, Travis hit .359 with 19 triples and 101 RBIs. Then he went to war.

Travis played ball while his unit, the 76th Infantry Division (the “Onaways” who lost to the “Red Circlers” in the ETO semifinals), trained stateside, but once in Europe, he saw action. In January 1945, the 76th was rushed into combat at the Battle of the Bulge, fighting the onrushing 212th Volksgrenadier Division in the woods of Belgium. The extreme cold was as bitter an enemy as the Wehrmacht. It felled Travis, a southerner from rural Georgia who had rarely spent a day in freezing temperatures in his entire life.

“Heck, you was in that snow,” he recalled some years later, “and you was out in that weather, and if you was lucky you got to stay in an old barn at night. The thing about it, you’d sit there in those boots, and you might not get ’em off for days at a time. And cold! You’d just shake at night. Your feet would start swelling, and that’s how you’d find out there was something really wrong—you’d pull your boots off, and your feet is swelling.”

Something was wrong, all right—when doctors got a look at his frostbitten feet, Travis was rushed into surgery. Fortunately, it was in time to save his feet—without the operation, they would have been lost. Yet he wasn’t immediately discharged—Travis was transferred to the Pacific Theater, but the war ended before he shipped out.

Travis returned to baseball, but he wasn’t the same player he was before the war. He had lost the ability to transfer his weight at the plate thanks to his operation, and nearly four years away from the game had robbed Travis of his timing. He hit only .252 in 1946. The classy, unassuming star retired after the 1947 season, but not before a “Cecil Travis Night” was held in the nation’s capital, attended by several military luminaries, including General Eisenhower.

The Battle of the Bulge ended with the Allies beating back the Nazi counteroffensive in January 1945. Two months later, on March 7, 1945, the Allies launched “Operation Lumberjack,” an effort to seize the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen and establish a toehold on the other side of the Rhine. It was a critical strategic turning point in the invasion of Germany. The army got across the river and held the bridgehead, despite fierce bombardment from German artillery and air power.

On March 17, army engineers were swarming the bridge, trying to repair damage from the German shells, when the structure collapsed. Twenty-eight engineers were killed, many of them swept away by the Rhine current. Ninety-three more were injured.

One engineer was yards away when his fellow bridge builders fell to their deaths. This soldier narrowly missed becoming the third major leaguer to perish in action during the war. He survived to return to the Boston Braves, where he would win eight games in 1946, including a three-hit shutout of the Cardinals that presaged his future brilliance. His Hall of Fame career would begin in earnest in 1947, encompassing 363 wins by the time it was over, more victories than any lefty in baseball history.

His name was Warren Spahn.

Spahn grew up in Buffalo, New York, the son of a wallpaper salesman, and made it to the Braves in 1942.

He only tossed a handful of innings before his manager pulled him from a game for refusing to brush back Pee Wee Reese, who recently had been beaned. That manager, Casey Stengel, told Spahn he was “gutless,” and sent him down to the minors while the game was still being played.

At season’s end Spahn enlisted in the army. At first, he played baseball, hurling a no-hitter in a game at Camp Chaffee, Arkansas. But he shipped out to Europe with the 276th Combat Engineer Battalion in 1944. “Let me tell you,” Spahn said, “that was a tough bunch of guys. We had people that were let out of prison to go into the service. So those were the people I went overseas with, and they were tough and rough and I had to fit that mold.” Spahn brought a baseball mind-set to unit security. Hyperaware of Germans wearing American uniforms, Spahn would challenge anyone who approached his position. “Anybody we didn’t know, we’d ask, ‘Who plays second for the Bums?’ If he didn’t answer ‘Eddie Stanky,’ he was dead.”

Spahn fought in the same frozen Belgian woodlands that did a number on Cecil Travis’s feet during the Battle of the Bulge. He was hit by enemy fire, once in the head and once in the stomach, minor scratches both, albeit millimeters from being grievous if not mortal wounds. “We were surrounded in the Hertgen Forest and had to fight our way out of there,” Spahn recalled. “Our feet were frozen when we went to sleep and they were frozen when we woke up. We didn’t have a bath or change of clothes for weeks.”

The Victory Season

The Victory Season