- Home

- Robert Weintraub

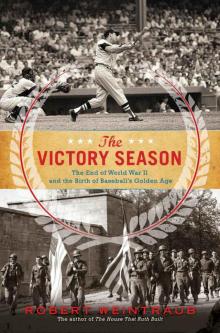

The Victory Season Page 36

The Victory Season Read online

Page 36

Grover Cleveland Gilmore, the fan who had passed out cold after waiting two days on the ticket line at Fenway, had become a press sensation, and the Globe did its part, picking up the tab for Gilmore to fly to St. Louis. Gilmore required special fortitude to get there, as he had never flown before. Originally booked on American Airlines, the flight was canceled due to “traffic conditions.” Eastern, Trans World, Northeast—all came up empty. Desperate, he was about to cancel when United got him on a flight west. “I felt a little shaky,” he admitted, but he felt better during a photo op with his namesake, Grover Cleveland Alexander, the Hall of Fame pitcher.

In more poignant news, Harry Walker learned that he had a new daughter. Carole Walker was born back in Leeds, Alabama. After the huge scare when his son, Terry, was hit by the car, Walker was eager to get down south as soon as possible to be with his injured boy. At the same time, he was certain he would play a big role in the denouement of the Series, especially now that a flaw in his stance had been ironed out. It was Dixie who had seen it when the Dodgers played the Cards in September, when Harry was slumping badly. “You’re lunging and taking your eye off the ball,” big bro counseled, despite the pennant race. “Try pulling your feet together. It won’t seem natural at first, but it works.” Sure enough, the Hat started to hit, just in time for the postseason.

Housing, or lack of it, dominated the off-day talk, as it had throughout the year in all walks of life. The playoff delay meant the Series now collided head-on with a Missouri medical examiner convention and state PTA conferences, which took up most of the available hotel space. Folks already ensconced in their rooms refused to vacate for incoming baseball fans, with the result that a great number slept in cots in hotel dining rooms, or on park benches, or not at all.

That was certainly the case in the area surrounding Sportsman’s Park, where once again the ticket lines took over. “Early [Sunday] morning, Sullivan [Street] near Grand [Avenue] looked like a bivouac, with a dozen fires blazing along the ball park wall,” reported the Post-Dispatch. “Fans waiting for tickets stood around the fires, heads wrapped in blankets,” to ward off the chill, down below freezing.

A crowd of 35,678 got into the ramshackle old park for Game Six, creating a roar that began about an hour before first pitch and never let up. The chill had once again been burned off by an Indian-summer sun, and the warmed crowd let loose with a fusillade of noise, including a police siren that sounded regularly in the right field corner. The cacophony went on despite the absence of Mary Ott, the leather-lunged fan, who was sick and frustratingly unable to attend the season’s final home stand.

Fans were asked not to bring boxes, stools, or chairs inside, as they had in the first two games. And a “one fan per step” in the aisles policy was strictly enforced. The throng strained to hear Benjamin Rader, whose band was fresh off a well-received appearance at the signature St. Louis event of the season, the Veiled Prophet Ball, play “To Each His Own,” and other tunes before the game.

Down in the clubhouses, a drama was unfolding that for some players was every bit as important as the game to follow. The small Series pool, from which shares would be paid out to each player, was originally meant to be augmented by the money Gillette paid baseball for the radio rights to the Series. Instead, that cash was now ticketed for the nascent pension fund, and several Boston players were pissed about it. Marty Marion, the driving force behind the plan, spent several minutes in the enemy clubhouse trying to change the minds of the holdouts, while Pinky Higgins gave an impassioned speech on behalf of players who had already retired from the game. The browbeating worked—the Sox voted unanimously before the game in favor of the plan. On his way out to the field for the game, Marion gave Happy Chandler a thumbs-up—a new pension system was ready to go.

Brecheen was the obvious starter for St. Louis. Hughson seemed the equally likely starter for the Sox, but Cronin mysteriously went with Harris, announcing that he wanted to save Hughson for Game Seven if things went south. Considering Ferriss was ready to go for Boston the next day, it seemed a curious stratagem—holding back the staff’s second-best hurler in case the ace needed bailing out. Cronin’s gamble to start Dobson and rest his top two in Game Five had paid dividends, thanks to his “Celtic ancestry.” In the words of Arthur Daley, “He consulted with Leprechauns.” Now, he was playing his hunch once more.

To Dyer, it was defeatist thinking he would never have countenanced. He gleefully accepted Cronin’s largesse, saying, “We got to Harris once and we can get to him again.” It was another way to give his team the psychic edge. See? he could tell his team. They still think so little of you guys in the opposing dugout that they’re sure any of their pitchers can beat you! “These Cardinals are not a Gashouse Gang,” noticed Harold Kaese. “Eddie Dyer had made them a team of psychologists. They beat your brains out with a plush-covered window weight, instead of a hammer.”

But it was the Cat who struggled at first. Boston loaded the bases in the first inning, and Dyer had Red Munger warming up as York strolled to the plate with one out. But Brecheen got him to hit into a double play, and Munger sat down.

A sacrifice fly from Moore got the Cards on the board first. Later in the third inning, Musial came up with two out and a man at second. He bounced one to deep short, and legged out an infield hit. “You’d swear he was just a .210 hitter happy to have a slim chance to get on,” thought the Post-Dispatch, commenting on the way the usually staid Musial pumped his fist upon beating the throw. Kurowski followed with an RBI single to make it 2–0 Cards.

Slaughter received a tremendous ovation when he first ran onto the field, and got an even larger salute now as he dug in to face Harris. Up in the stands, Dr. Hyland held his breath. “I said to my neighbor, ‘there is a boy diving himself out of baseball,’” he said later. Country, whose attitude was summed up with a pregame “to hell with my right arm!” gunned the first pitch he saw back up the middle to score Musial and chase Harris from the game (Enos would aggravate the cursed arm again on a pickoff, and need more X-rays after the game). Cronin glumly went to replace Harris with Hughson, wondering what would have happened had the tall Texan started the contest, especially after Hughson shut out the Birds on two hits over the next four innings. Harris went berserk in the Boston clubhouse, slamming his glove on his locker over and over and kicking his civilian clothes to the floor.

The choice of starter would haunt Cronin well after the Series. As the Times put it, “There is nothing sadder in baseball than the hunch that goes astray.” Daley went back to the Irish well for his commentary: “The Leprechauns…gave him a bad steer this time. Perhaps Joe feels—the meat shortage being as acute as it is—that a bad steer is better than no steer at all.”

For his part, Brecheen was once again mystifying the Sox lineup, conducting a master class in changing speeds and eye level. No less an authority than Harry’s wife, Vera, had pointed out to Broeg that Brecheen had faced most of the Boston hitters in the minors and knew how to attack them. Williams, who hadn’t hit a ball out of any park since September 11, agreed with Mrs. Brecheen. “They certainly know how to pitch to me, cause I’m getting what I’m not expecting.” Ted managed his fifth hit of the Series, another single, in the ninth with Boston down 4–1, but York hit into another double play to end the game. “Cronin should send his regulars to the zoo, lure them into cages, and replace them with orang-outangs [sic] who can hit,” suggested Kaese.

Dyer’s first words to the Cat in the happy Cards’ clubhouse were “I wish you were twins.” Brecheen had been masterful once more, giving up only three hits over the final seven innings. “The Red Sox have some fine hitters when you give them what they want,” he said, as a 78 of “Woodchoppers Ball” had the happy squad dancing around the room. “But I didn’t do that.” Photographers made Slaughter and Schoendienst kiss the Cat over and over again for the cameras. “He doesn’t get this many from his wife,” cracked Country, happy to hear the X-rays were negative once more. For his part, Willia

ms’s ghostwriter Hy Hurwitz used some grisly feline flavor in “Ted’s” column. “The Cat not only skinned us again, but he feasted on our flesh and scratched on our bones.”

The Cat was so effective he overcame a major faux pas from Cards’ PA announcer Charley Jones. As Brecheen warmed up for the ninth, he heard Jones tell fans that tickets for Game Seven would be available for sale the following day. The St. Louis dugout, aware that Jones had just spit at the baseball gods, were apoplectic. “We were ready to shoot that guy,” recalled Munger. But superstition was no match for the Cat’s stuff.

The season, appropriately and to the consternation of many writers, would last as long as possible and be decided by an all-or-nothing Game Seven. The World Series was “in the laps of the Gods,” as the Times put it, and the immortals had been capricious indeed through six games.

Chapter 39

The Mad Dash

The Series took Monday, October 14, off, so the Cardinals would have a full day to sell tickets for Game Seven. The late notice combined with the beginning of the workweek to prevent mass hysteria, but the expected thousands lined up for the chance to witness the deciding game. Anything was likely to happen Tuesday afternoon. As Daley had written in the Times, “This has been such an astonishing and incredible show that no one would raise an eyebrow if the Mississippi River suddenly changed its course and carried Sportsman’s Park out to sea—not a bad idea at that.”

Cardinals fans jamming the streets passed around rumors. A story that Louis B. Mayer of MGM Studios fame wanted to buy the Cardinals and move them to Los Angeles had spread like wildfire during the Series. Breadon had to announce that he had no intention of selling. Of more immediate concern was that Slaughter supposedly was out after aggravating his injury. Country spent most of the day with his elbow wrapped tight, and he missed the light workout the Cards held around noon. But short of a fresh bullet wound, there was no chance Slaughter was going to miss Game Seven. “The weak fall by the wayside, the strong shall carry on,” he said, laughing, while stretched out on the clubhouse rubbing table.

Another worried word passed around the streets of downtown St. Louis was that Williams had found his groove in batting practice and was smashing homers left and right. In fact, Ted was busy getting tips from Tex Hughson, of all hitting experts, who called the Splinter over after a session in the cage and advised him to correct part of his stance. Ted told reporters that he had received a letter from a fan calling the Dyer Shift “a crime” and that “It’s up to you to make crime pay.” “That’s what I’m trying to do tomorrow,” he said, laughing. The Cards’ manager was also hearing it from fans complaining about his “gangster tactics” that were “bound to upset the poor fellow” (meaning Williams). Dyer didn’t signal any inclination to change his strategy due to hate mail.

After the workouts, the players mostly hit the cinema to avoid thinking about the game the next day. The Big Sleep (“Bogie and Bacall, together again! Terrific again!”) had just been released and was a popular choice among baseball people looking to kill time. The Best Years of Their Lives, the big hit of the year that captured elements of the nation’s difficult postwar homecoming, was no longer in theaters, so other popular choices were Nobody Lives Forever with John Garfield at the Ambassador or Ava Gardner in The Killers at the Fox. The Cardinals were probably less partial to Danny Kaye as The Kid from Brooklyn and to Mr. Ace, which starred Leo Durocher’s buddy George Raft.

Judgment at Nuremberg was still fifteen years from being made, but the events that made up its final reel were unfolding in Germany even as the teams got ready for Game Seven.

The condemned Nazis in Major Teich’s secure military prison in Nuremberg spent their final hours supping on a traditional German meal of potato salad, sausage, cold cuts, black bread, and tea. Most read Bibles, except Hermann Goering, who paged through Theodor Fontane’s novel Effi Briest.

The creator of the Luftwaffe knew he didn’t require help from above. He had assistance on the ground. A nineteen-year-old guard named Herbert Lee Stivers had befriended Goering during the long months of trial. “Goering was a very pleasant guy,” Stivers told the Los Angeles Times in 2005, when he at last came forward with his story, one that unlocked a mystery that had confounded historians for six decades. “He spoke pretty good English. We’d talked about sports, ball-games. He was a flier and we talked about Lindbergh.” As Stivers walked Goering to and from the courtrooms in the Palace of Justice, he never thought that his prisoner would contemplate suicide. “He was always in a good frame of mind.”

Outside the prison, Stivers had met a beautiful, dark-haired local girl. Seeking to impress her, he gave her an autograph of his imprisoned charge. The girl, apparently named Mona, introduced Stivers to a pair of her friends, named Erich and Mathias. They asked Stivers to pass Goering notes hidden in a fountain pen. Seeing no harm, he agreed. A few days later, after the death sentence had been announced, they asked Stivers to smuggle in some “medicine.” Stivers agreed, saying he would bring the empty pen to Mona the following day. He never saw her or the men again.

Stivers had unwittingly brought Goering a capsule of potassium cyanide, which Goering crunched down on early in the morning of October 15, hours before he was set to meet the hangman. He lay down on his cot, began twitching, and died almost instantly.

The American guards were dumbfounded. Goering’s person and cell had been searched almost daily. A guard examined everything ever handed to him, including food, and a blue-helmeted MP was never more than three feet away. The light burned twenty-four hours a day in his cell, and he was not allowed to sleep with his face to the wall, turned away from the guard outside. His hands had to remain above his covers while he slept. Yet despite the claims that “suicide was impossible” at the prison, there was Goering, barefoot in a blue pajama top and black silk bottoms, dead on his bed, having cheated Allied justice.

He was the only one. The other Nazis were manacled and marched into the prison gymnasium, where three gallows had been erected. Von Ribbentrop, a man who once compared Jews to crop pests that should be eradicated similarly, was the first man hanged, shortly after one a.m. local time, or six p.m. St. Louis time. He shouted, “God save Germany! My last wish is that Germany rediscover her unity and that an alliance be made between East and West and that peace reign on Earth!” as the trapdoor swung open. No photos or movies were allowed to capture the hangings. Reporters watched through binoculars from an attic opening seventy-five yards away. It took seventy minutes to hang all ten prisoners, as many fell with not enough force to break their necks. One, General Wilhelm Keitel, took a full twenty-four minutes to strangle to death.

As Robert Conot, the author of Justice at Nuremberg (upon which the movie was based), wrote, “It was a grim, pitiless scene. But for those who had sat through the horrors and tortures of the trial, who had learned of men dangled from butcher hooks, of women mutilated and children jammed into gas chambers, of mankind subjected to degradation, destruction, and terror, the scene conjured a vision of stark, almost biblical justice.”

Harry Brecheen was too sick to chew over how Goering had managed to kill himself. He showed up at Sportsman’s Park on the morning of Tuesday, October 15, feeling god-awful. He had been surrounded by the press after Game Six, and by the time he finally got to shower, all the hot water was gone. Chilled, he found his immune system was riven by a virus. “I had a fever and a cold and my head was about to bust open,” he said. At least he wasn’t going to have to pitch, since he had gone nine innings two days before. The Cat “filled up on aspirin,” bundled up despite the warm weather, and plopped on the bench.

Murry Dickson would be the man to carry the hopes of St. Louis, the greater Cardinals Nation, and the entire National League on his slender right arm. Thanks to the extra off day, Ferriss would get the ball after a long six-day layoff. Sadly, no one thought to pose the two starters together for a photo. As Dickson only rose to Ferriss’s shoulder, the photog would have had to back up considerabl

y to frame them.

It was another glorious day, with a brilliant autumn sun slanting through fleecy white clouds. Temperatures soared into the mid-’70s. Undaunted, many women in the crowd of 36,143 wore fur coats, as befit such an august occasion. The official attendance reflected the ticket sales, but there sure appeared to be many more than that number in the house. Ramps were jammed tight, concession stands blocked. Few had decent standing-room vantages. Most offered just a sliver of the outfield green for a view. Fans eluded the rule barring chairs and boxes by piling seat cushions four and five high and standing on them in the aisles. The stands were packed so tight some writers needed a full half hour to climb the stairs to the press box. One sweat-covered man complained that “they must have sold four tickets for every seat.”

Back in Boston, thousands jammed the Common to listen to the game broadcast over public-address speakers at the Parkman Bandstand, and many thousands more filled the Hatch Memorial Shell down by the Charles River, where the Boston Pops usually drew the crowds. Vendors sold refreshments to the masses, mostly cold drinks, as the afternoon was unseasonably warm in Beantown. Fans who had braved the chilly games at Fenway cursed their luck.

Breadon had used the off day to order his minions to scour the countryside for meat and booze for the press boys, and so the writers had a sumptuous feast for lunch. It was so nice, Breadon and Yawkey ate there as well. Given the sky-high costs of the fare, one reporter estimated the Cards owner had spent about twenty grand (over $200,000 today) on the huge spread, a stunning display of largesse from the tight-fisted owner.

The Victory Season

The Victory Season